Things I got to learn travelling Ladakh on a cycle

When people think of Ladakh, the first thing that often comes to mind is tourism. Known for its stunning Himalayan landscapes, including the Nubra and Zanskar valleys and the breathtaking Pangong Lake, Ladakh is a popular holiday destination. However, there is much more to this region than tourism, aspects of which are often overlooked.

Ladakh is divided into two districts, Leh and Kargil, and only achieved Union Territory status in 2019. These districts are culturally distinct, with Leh being predominantly Buddhist and Kargil largely Muslim. Life in Ladakh is harsh and challenging, far more than one might expect. Situated at an elevation of over 10,000 feet above sea level, the region experiences reduced oxygen levels due to the sparse vegetation and dry mountain landscape. Wind speeds can exceed 100 km/h in many areas, and for about four months each year, heavy snowfall effectively halts daily life, confining locals to their homes.

Beyond these environmental challenges, Ladakh’s political situation is tumultuous. The revocation of Article 370 and debates over the Sixth Schedule have led to protests, reflecting the complex political dynamics locals face. The geographical reality is that Ladakh, as depicted on Indian maps, is partly occupied by China on one side and Pakistan on the other. Employment opportunities for locals are limited mainly to construction work by the Border Roads Organization and army camps.

Unfortunately, there is little regulation of the growing tourism industry and its impact on the environment, notably accelerating glacier melts. Tourists often remain oblivious to these critical issues. In this article, I aim to share my experiences and insights from traveling in Ladakh. While I strive to present an unbiased view, my perspective is inevitably shaped by my travel methods and personal outlook. I apologize for any information that might seem inappropriate to some readers and invite you to contribute your thoughts and insights by commenting below.

WAY OF LIFE

During my travels, I found the people of both Leh and Kargil districts in Ladakh to be some of the kindest I’ve ever met. In Leh, simply greeting locals with the word “juley,” their traditional greeting, can open the door to a warm and friendly conversation. Meanwhile, in Kargil, even without a greeting, visitors are met with hospitality and kindness.

Ladakh, known for its reliance on tourism, might seem like a place where overpricing is common. Given its remote location and the logistical challenges of transporting goods, higher prices are often expected. However, I found that in Kargil, people rarely overcharge, even when they have the opportunity to do so. On several occasions, vendors in Kargil called me back to return change after realizing a miscalculation, showing an honesty and integrity that was truly refreshing. In some instances, they even waived small amounts because they didn’t have the exact change, demonstrating their goodwill.

Kargil felt like a place where the thought of cheating didn’t even enter people’s minds, even if such practices were more common elsewhere, including in Leh. The genuine honesty and warmth of the people in Kargil left a lasting impression on me, highlighting the unique and admirable character of its residents.

Language

In Ladakh, the primary language spoken is Ladakhi, which has various dialects depending on the region. However, the linguistic landscape in Kargil is notably more diverse. In Kargil, three distinct languages are spoken: Balti, Purkhi, and Sheena. Each language becomes more prevalent from east to west across the district, reflecting the cultural and ethnic diversity of the region.

Interestingly, none of these languages have their own unique script. The Ladakhi language is typically written using Tibetan script, highlighting the historical and cultural connections between Ladakh and Tibet. This connection dates back to the time when Ladakh was part of the neighboring Tibetan kingdom until it established its own monarchy in the 9th century. This historical tie explains the Tibetan influence not only in the use of the Tibetan script but also in the cultural and religious practices observed in Ladakh.

The influence of Tibetan culture is evident in education as well. The Boti script, which is the Tibetan script, is taught in schools and monasteries across Ladakh. This script plays a crucial role in preserving the region’s Buddhist heritage and teachings. In contrast, the Muslim communities in Kargil learn to read and write in Urdu, which is taught in schools using the Perso-Arabic script. This script is also used for writing Balti, Purkhi, and Sheena, reflecting the Islamic cultural influences that have shaped the region.

Crops

The Leh district of Ladakh is characterized by its arid and dry climate, making farming a challenging endeavor. This is particularly true in the eastern part of the Union Territory, where agriculture is sparse due to the harsh conditions. However, in the western part of Ladakh, barley becomes a significant crop. This is reflected in local traditions, such as the preparation of a traditional drink made from barley, which is often served during marriages and other ceremonies.

Aside from barley, a limited variety of vegetables are cultivated in Leh, primarily turnips, potatoes, and peas. These are grown in small quantities, and most vegetables need to be imported from the neighboring state of Kashmir. This reliance on imports is largely due to the limited agricultural output in the region and the logistical challenges posed by the harsh climate. The Srinagar-Leh highway serves as the primary route for transporting goods for most of the year, as the Manali-Leh highway is closed during the winter months due to heavy snowfall.

The cost of transporting vegetables from Kashmir significantly inflates their prices in Leh. During the winter season, the price of essentials such as tomatoes can skyrocket to as much as 250 rupees per kilo. This economic strain contributes to the tensions between the Ladakhis and their Kashmiri neighbors, as the high prices of goods are a persistent issue.

In Leh, the primary source of food comes from livestock, with shepherds playing a crucial role in the region’s economy. These shepherds rear cattle, particularly sheep and yaks, and they belong to nomadic tribes that migrate throughout the year in search of suitable grazing lands. During the winter, they move to places like Chagar Lake, which receives less snow, providing more hospitable conditions for their herds. Among their livestock, the Pashmina sheep, known for producing the luxurious cashmere wool, are particularly valuable. These sheep are considered the most expensive in India, and their strength and health are attributed to the medicinal plants they graze on in the mountains. The shepherds possess extensive knowledge of these medicinal plants, which are an integral part of their traditional lifestyle and practices.

In contrast, Kargil is known for its agricultural activities, with apples and apricots being the predominant crops. The region’s farmers focus more on cultivating these fruits rather than raising cattle, marking a distinct difference between the agricultural practices in Leh and Kargil. The abundance of these fruits underscores Kargil’s identity as a primarily agrarian community, contributing significantly to the local economy and way of life.

Food

The cuisine in Ladakh is distinct and quite different from what one might find in other parts of India. One of the most notable beverages is butter tea, which is also popular in the neighboring regions. This unique tea, made from tea leaves, butter, and salt, is a staple in Ladakhi households, providing warmth and energy in the cold climate.

Ladakhi dishes generally contain little to no masala, reflecting the simple and hearty nature of their diet. Many dishes are made from atta (wheat flour) and locally grown vegetables. A staple dish in Ladakh is Sku, a comforting and nutritious meal prepared in a soupy fashion using atta and vegetables. Other popular dishes made from atta include Timok, Chutagi, and Thukpa. Thukpa, in particular, is a hearty noodle soup that is widely enjoyed for its warmth and sustenance, especially during the cold months.

In addition to these atta-based dishes, rice is also consumed, usually in one of the daily meals. Sattu, a form of roasted chickpea flour, is favored for its health benefits and its ability to help retain body heat, making it a practical choice in the cold Ladakhi climate.

In the Kargil district, the culinary traditions include a variety of breads. People here commonly consume leavened bread, deep-fried buckwheat bread, and pancakes, often accompanied by butter. These breads form an essential part of the local diet, offering a rich source of carbohydrates and energy.

Meat is also a regular part of the diet in both Leh and Kargil districts. Given the region’s harsh climate and limited growing season, meat provides an important source of protein and calories, supporting the high-energy needs of the local population. The inclusion of meat in meals reflects the nomadic and pastoral traditions of the region, where livestock plays a central role in daily life.

Lifestyle

The people of the Leh district in Ladakh are generally known for their reserved nature, often preferring to keep to themselves and speak minimally with outsiders. This reticence is a characteristic of their culture, though it has been gradually changing with the region’s development and increasing tourism. As Ladakh’s tourism industry has grown, so have the local economy and living standards. This economic development has influenced the younger generation, who are now more educated and less inclined to follow the traditional path of becoming shepherds.

To preserve this cultural heritage, the government is actively promoting shepherding by providing subsidies and constructing tents for shepherds across the hills, encouraging this age-old practice. Notably, about 20% of the Leh district’s population consists of Tibetan migrants, who have received substantial support from the government. They have established their own schools throughout the district, fostering harmony between the Tibetan and local communities.

Interestingly, the Buddhist community in Ladakh exhibits some elements of casteism. The “tompa” caste is considered superior, while the “lohar,” “daman/beda,” and “mon” castes are viewed as lower, typically engaging in professions like blacksmithing and drumming. This social hierarchy is an intriguing aspect of the region’s cultural dynamics.

In Leh, it is common to see many second-hand vehicles with registrations from lower states such as Delhi (DL), Punjab (PB), and Haryana (HR). This trend is partly due to the affordability of these vehicles and the absence of strict vehicle checks by local authorities.

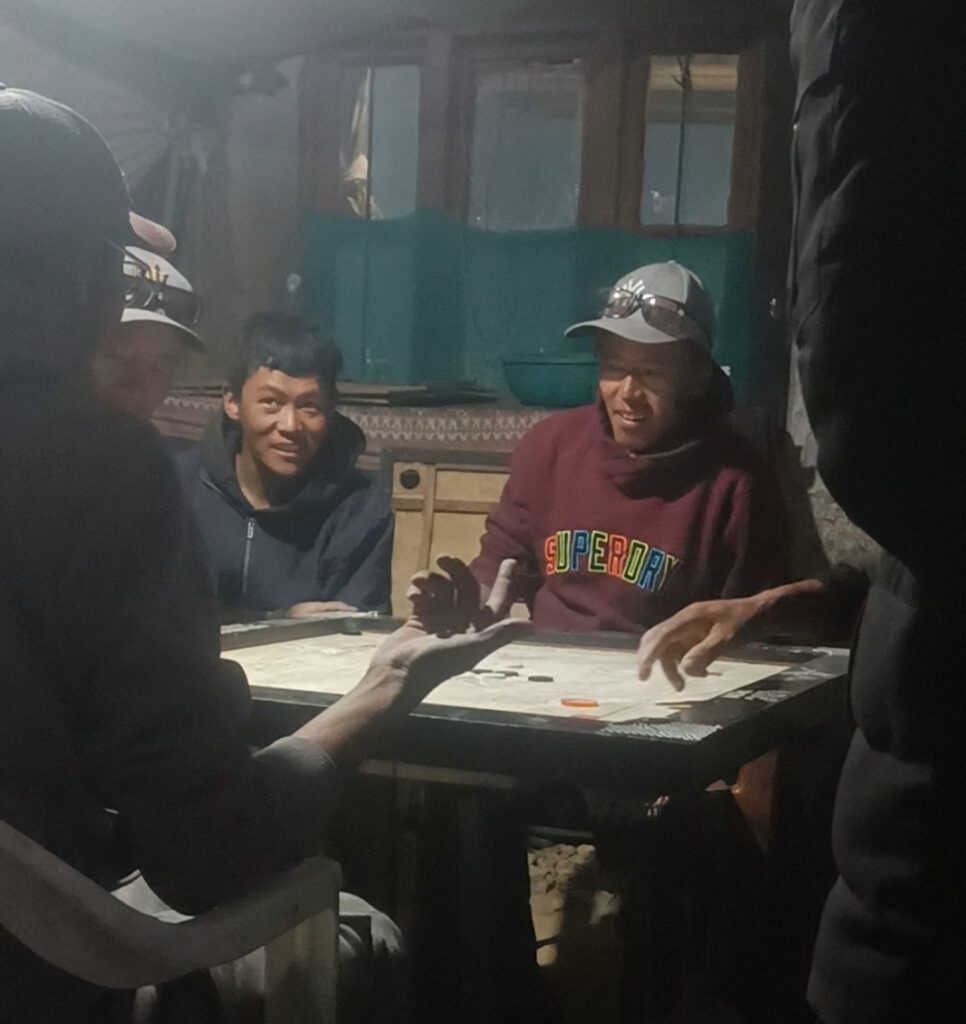

The availability of phone networks and internet connectivity in Ladakh is a relatively recent development. Before this technological advancement, locals would gather in the evenings to play cards and carrom for entertainment—a tradition that persists in many areas, though it is reportedly diminishing over time. With a total population of approximately 300,000, the vast, open spaces of Ladakh offer ample opportunities for camping and picnics in the grasslands along riverbeds. This picnic culture is reminiscent of similar practices observed in Telangana.

During the harsh winter months, when snow blankets the region for about four months, people in Leh historically remained indoors with stocked rations. However, as the number of middle-class residents has increased, many now choose to relocate to lower parts of India during the winter.

Leh’s residents have a strong appreciation for music and dance, and they eagerly participate in festivities when the music starts. Originally a tribal community, Leh has a rich cultural heritage of music and art, showcased during the annual Nomadic Festival in Ladakh.

In the Kargil district, despite being predominantly Muslim, the people share Asian features similar to those in Leh. Their cultural practices, however, are more akin to their Kashmiri neighbors, with whom they share the Islamic faith. Kargil was a focal point during the 1999 war against Pakistan, and many areas bear the scars of that conflict. Locals take pride in the role their community played in supporting the Indian army during the war to repel Pakistani forces. They are staunch supporters of the Indian army and generally harbor strong feelings against Pakistan and its governance.

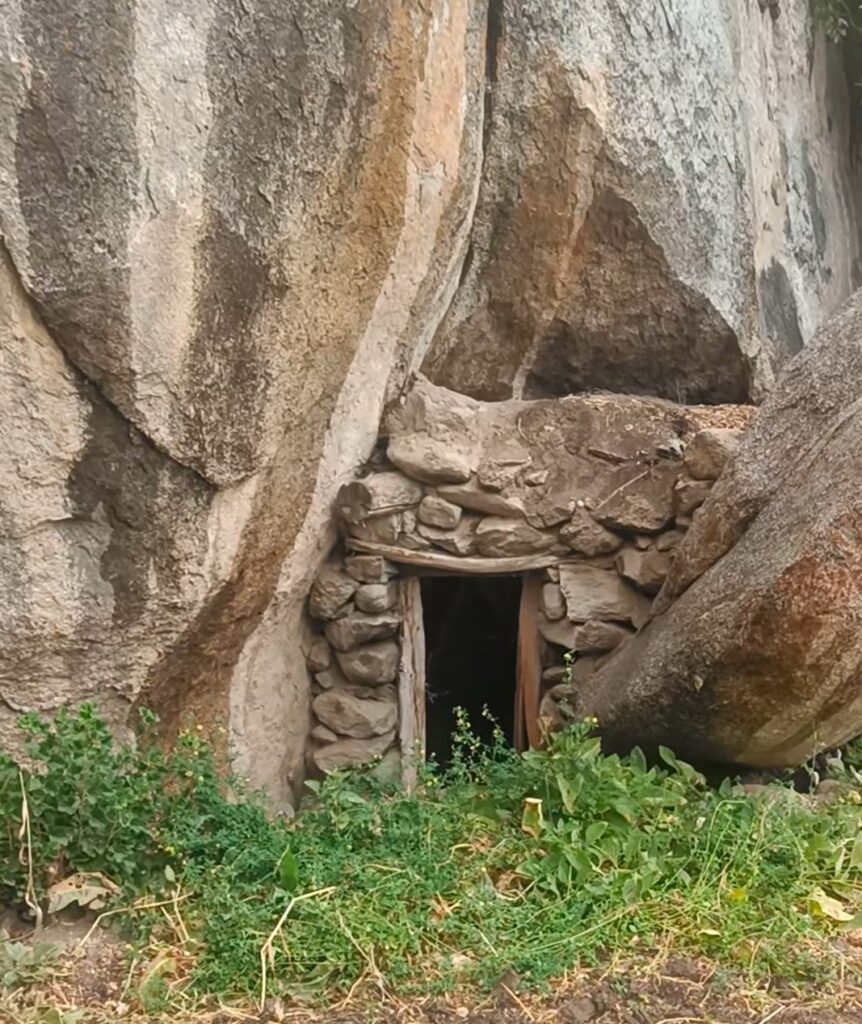

While Kargil’s residents are primarily farmers, they emphasize that their ancestors built the region with their own hands. As such, they express concerns about the Indian government’s claims over their land for development purposes, advocating for the reinstatement of Article 370 to ensure their land rights. This demand underscores the ongoing tension between preserving cultural heritage and accommodating modern development, as discussed in another section of this article.

THE TOUGH CONDITIONS

Ladakh is considered one of the most challenging places to live in India due to its harsh climate and rugged terrain. Despite the region’s rapid development, particularly in terms of its roadway network, significant challenges remain. One of the most pressing issues is the lack of electricity across the Union Territory, especially in the eastern part, where power lines are scarce. Although some roadways have been constructed recently, many areas still lack proper infrastructure.

To accommodate the influx of tourists, tents with minimal facilities have been erected. These tents often lack basic amenities such as running water for washrooms. Electricity is typically provided by fuel-powered generators, which are only turned on for a few hours between 7 and 10 PM to provide lighting.

While the local population of Ladakh is around 300,000, it is estimated that the number of outsiders, particularly those working for the Border Roads Organisation (BRO), is more than ten times that figure. Many of these laborers hail from states like Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Bihar, and they often struggle with the lack of oxygen at high altitudes, which makes them short of breath after only a few steps. Residents of Kargil have also noted that many elderly locals suffer from asthma due to the thin air.

The absence of a comprehensive road network contributes to a high rate of accidents in the region. Trucks involved in accidents are frequently seen abandoned by the hillsides because they are difficult to remove.

The locals rely heavily on glacier water for their needs, which means that a lack of snowfall can lead to severe water shortages. Some residents must walk long distances to fetch water, and during winter, water sources freeze, requiring it to be melted for daily use.

Army camps stationed in the mountainous border areas endure extreme winds that can exceed 180 km/h, sometimes blowing away their campsites. Locals employed to transport water to these remote army outposts drive trucks in three shifts daily, earning up to 80,000 rupees a month for this essential service.

During the winter, when snow covers the entire region, both civilians and army personnel must stock up on essentials, making it difficult to maintain daily life outside of enclosed spaces.

Despite these formidable challenges, the Border Roads Organisation is tirelessly working to expand the road network, connecting even the most remote corners of Ladakh. This development is expected to facilitate better connectivity for military operations and tourism. In the coming years, improved infrastructure will make even the most isolated areas of Ladakh accessible to the public, enhancing the living conditions for both locals and army personnel stationed in the region.

POLITICAL SCENARIO

Despite the apparent growth and development in Ladakh, the region is embroiled in national and political turmoil. Many Indians might not realize that the map they see on their phones and in atlases does not accurately reflect the true boundaries of India, as significant portions of Ladakh are occupied by either China or Pakistan. In 1962, China advanced and took control of the Aksai Chin area in eastern Ladakh. Now, the entire northern section of the Indus River is under Chinese occupation, bringing our neighbors closer than many realize. Recently, China has moved further, occupying Kala Pahad (Black Hill) near Demchok, at the border with India.

During my travels to these remote areas, I observed rapid development on the Chinese side, with electricity lines and well-developed transportation networks. This stark contrast highlights the challenges India faces in defending its territory in the event of an invasion. If a conflict were to arise, our current preparedness might be insufficient, leaving us vulnerable to being overrun before reinforcements can arrive. The construction of Umling La Pass, the highest motorable pass in the world, aims to strengthen our borders and improve accessibility. However, based on my observations around army camps near the border, India is not yet equipped to handle a full-scale Chinese incursion.

Politically, Ladakh is experiencing significant unrest due to the recent revocation of Article 370 and the 6th Schedule, both of which were intended to protect the region’s unique status. Article 370 granted special autonomy to Jammu and Kashmir, including Ladakh, preventing outsiders from settling and buying land there. Its removal by the government is viewed by locals as a political move that threatens to open the region to industrialization and an influx of outsiders, potentially reducing locals to mere laborers. This change also risks eroding the region’s culture and environment, especially as tourism continues to grow, as discussed elsewhere in this article.

The removal of the 6th Schedule, which would have granted Ladakh tribal status, further undermines local autonomy over sustainable development and cultural preservation. Sonam Wangchook, a prominent local figure, has been actively raising awareness and protesting against these changes throughout Ladakh. The Ladakh Buddhist Association is also fighting hard to restore these protections.

Residents of both Kargil and Leh districts, along with those from neighboring Jammu and Kashmir, are demanding the reinstatement of Article 370 to ensure their state remains secular, despite the government’s assertion that the article was intended only as a temporary, transitional measure. During the Jammu and Kashmir regime, Ladakh was often neglected, with most resources funneled to Kashmir. Although the Union Territory’s budget has increased significantly, locals prioritize the implementation of the 6th Schedule in Leh and the restoration of Article 370 in Kargil over mere financial inflows. Interestingly, some funds have been returned to the government due to underutilization.

Amidst this political backdrop, the BJP government’s push for development in Ladakh is countered by the fact that Leh district supported the Congress party, resulting in the election of a Member of Parliament from the Muslim community. Locals claim that the previous Buddhist MP from the BJP was a strong advocate for Ladakh, supporting efforts to maintain its secular status. With the current MP from Kargil district, hopes for implementing the 6th Schedule in Leh seem to have stalled, leaving the region in a state of uncertainty.

TOURISM

During my conversations with the locals in Ladakh, it became clear that the tourism industry has only recently begun to flourish, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic. Previously, Ladakh was a niche destination, attracting daring bikers and a modest number of foreign tourists. However, in the past few years, Indian tourists have started to visit in large numbers, transforming the landscape of tourism in the region.

The initial post-COVID tourism boom prompted many locals to invest in the tourism sector by establishing homestays, restaurants, hotels, and transport service agencies. However, the anticipated surge in tourist numbers did not materialize as expected, leaving many businesses struggling with financial losses. The locals also expressed concerns about the gradual erosion of their nomadic culture as tourism grows in Leh. The younger generation is increasingly reluctant to herd sheep, leaving the mountains, once filled with grazing livestock, largely empty.

Fresh graduates in Leh shared their frustrations about the lack of job opportunities after graduation, which forces many into the tourism sector, causing them to abandon their traditional cultural practices. As a result, a growing number of young people are unemployed and idle, leading to concerns about the loss of the nomadic lifestyle that has defined the region for generations. In response, the government is making efforts to preserve this cultural heritage by providing tents for nomads at various locations in the hills, encouraging them to maintain their traditional ways.

Tourists visiting Ladakh today resemble those I have observed in Himachal Pradesh. While a few dedicated bikers, who have been exploring the hills for over a decade, continue to return, the majority are now renting vehicles or participating in packaged tours organized by travel agencies. This is evident from the numerous rented vehicles with black license plates on the roads. Most of these tourists are primarily interested in enjoying the scenic beauty, often staying in homestays or spending their days riding around aimlessly.

Unfortunately, many visitors arrive unprepared for the harsh conditions and suffer from Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS). I witnessed numerous tourists, including families with children, retreating to lower altitudes due to various symptoms. Visits to government-run primary health centers revealed that even in remote areas, up to 20 cases of AMS among travelers are reported daily.

While tourism provides a vital source of income for the locals, it comes at the cost of the region’s cultural heritage and environmental health. The influx of mindless tourists, often unprepared and unaware of the delicate ecosystem, threatens to erode the unique cultural identity of Ladakh and harm its pristine environment. This presents a complex challenge for the region, balancing economic opportunities with the preservation of its rich cultural and natural heritage.

OPPORTUNITIES

The quality of education in Ladakh faces significant challenges, with even students graduating from the top universities in Leh expressing dissatisfaction with the system. Many of these graduates struggle to find employment due to the limited job opportunities available in the region. In both Leh and Kargil districts, it is common for at least one member of each family to be employed by either the Indian Army or the Border Roads Organization (BRO). These are essentially the only sectors offering employment in Ladakh. Unfortunately, most individuals in these roles work as helpers or laborers, receiving minimal wages.

Within the BRO, there is a specific quota system for job allocation. Workers are assigned particular spots along the roads where they are responsible for maintaining cleanliness, earning a basic salary in return. This system, while providing some employment, does not offer significant financial benefits or career advancement opportunities. The scarcity of private sector jobs and other employment options contributes to the region’s economic stagnation.

The government’s focus on development, combined with the local push for safeguarding their traditional way of life and the rapid growth of tourism, creates a complex and challenging situation. The resulting lack of diverse job opportunities and the erosion of cultural practices highlight the delicate balance needed between economic progress and cultural preservation.

This raises critical questions about the role and effectiveness of education in areas where job opportunities are scarce. It also prompts a broader discussion about whether creating more job opportunities might inadvertently disrupt the unique cultural heritage of Ladakh. The challenge lies in finding a way to foster economic development while ensuring that the region’s rich cultural traditions are preserved and respected.

THE NEGLECTED TRUTH

Among the myriad issues facing Ladakh, one that has received scant attention is the environmental crisis. Ladakh offers a stark view of the effects of climate change, showcasing the rapid deterioration of natural landscapes. Unfortunately, many tourists remain oblivious to these changes, and government responses have been insufficient. Although Sonam Wangchuk has been vocal about the accelerated climate changes, his advocacy is often intertwined with demands for the implementation of the 6th Schedule, somewhat overshadowing the environmental urgency.

According to Kashmiri scholars specializing in glaciology, the Himalayan glaciers, including those in Ladakh, are melting at an alarming rate, making them the fastest receding glaciers globally. Three decades ago, glaciers in the region were melting at a rate of approximately one meter per year. Today, this rate has surged to between two and three meters annually, with some areas experiencing reductions of six to eight meters in just the past year. Historically, reductions in glacier mass were somewhat mitigated by intermittent heavy snowfall, but such occurrences have become increasingly rare. Current patterns indicate a troubling trend towards diminished snow cover and rising temperatures.

Local herders corroborate these observations, noting unprecedented heat and reduced water availability in areas that previously thrived. In Lamayuru, for example, a village has been forced to abandon sheep herding and agriculture due to the drying up of water sources. Long-time visitors to Ladakh, including seasoned bikers, report that routes which once opened in June are now accessible as early as April, reflecting the reduced snow cover and escalating temperatures.

Ladakh is a region of contrasts and complexities, offering a unique experience to those who visit. However, as its natural resources and cultural heritage face mounting pressures, the challenge remains to reconcile national, political, local, cultural, and environmental interests to preserve the integrity of this remarkable land. My observations reflect my personal experiences, and I encourage readers to share their insights or corrections in the comments below. For more articles on various states in India, please visit this page.

I am a 31 year young PhD graduate who has decided to travel the length and breadth of India on my cycle, to document the journey of meeting a vast array of people. In my journey, I intend to understand the characteristic features of the people of this nation and categorize them based on their demographics, age, profession, gender, traditions, and cultural differences.