Things I got to learn travelling Himachal Pradesh on cycle

Before starting this article, I must explicitly state that “All the states in India are one, but Himachal Pradesh is different.” Touring Himachal on a bicycle exposed me to a variety of life experiences I hadn’t encountered in the previous 12 states combined. The constant diversity from the north to the south of Himachal is mind-blowing. The southern region, Kinnaur, Spiti, and Lahaul each have their own unique flavors and essence, making it feel like you’ve crossed several different states within the nation.

From the exotic fruits grown in various parts of Himachal to the alarming rise of drug use, the state offers a stark contrast to travelers. Tourism is booming at an exponential rate, altering the demographics and cultures of many places. Just as Uttarakhand is considered Devbhoomi (land of the Gods), so is Himachal Pradesh. There are places in Himachal where land is owned by Gods rather than the government, and the word of the God, spoken by a human, is considered final.

Kinnaur and Spiti are worlds unto themselves. It would take a lifetime for an ethnographer to fully understand the nuances of these regions. Overall, I can only summarize my experience through my own eyes. I acknowledge that my perspectives are influenced by my mode of travel and personal biases. Please feel free to comment below and let me know if there is anything to add or edit.

LOWER HIMACHAL

The cash crops

As soon as one enters Himachal, they are greeted by vast apple orchards. People in lower Himachal are wealthy due to generations of apple and fig farming. The demand for farm labor has attracted poorer workers from Nepal and Uttar Kashi in Uttarakhand, who live and work on the farms while the landowners enjoy the profits. Families like Sanjeev Chauhan’s, who have been farming for generations, have amassed considerable wealth from these cash crops. The best quality apples are sold outside the region.

Cows are kept on the farms primarily for their dung, which is converted into manure, rather than for milk or ghee, which can be easily procured elsewhere. Typically, each orchard has three to four cows for manure production. Even the villagers in lower Himachal enjoy a prosperous lifestyle. While the eastern part of Himachal is known for its apple orchards, the western part boasts tea estates. All these cash crops thrive in the snowy regions.

Workers from Nepal are often integrated into the families they work for and are treated like family members. Each family usually employs a pair of workers, paying them 15,000 rupees each per month to tend the farms. Nepalis and Himachalis live harmoniously, with the Nepali workers becoming integral parts of the Himachali families they serve.

Education

People in lower Himachal prioritize their children’s education at all costs. Many residents find jobs in Punjab, resulting in a high flow of money back into Himachal. Nearly 100% of the population strives to educate their children, with many securing positions in the government sector. However, an increasing number of young people are returning to run their family businesses, finding apple farming to be more lucrative.

The population in this region is relatively low, partly due to the high level of education and the associated costs. Families often have only one child to manage the expense of education effectively.

Lifestyle

People in Himachal take immense pride in securing government jobs, often viewing it as a significant life achievement. Interestingly, many Himachalis predominantly own hatchback cars, a trend possibly linked to the recent accumulation of first-generation wealth, though this remains speculative. Notably, a significant number of Maruti 800s are still seen on the roads.

In lower Himachal, many houses and cabins are traditionally made of wood. Older homes, some over 200 years old, are constructed from Deodar tree wood, which is highly valued and considered sacred, as the Deodar is the state tree. These trees are revered and worshipped as deities. Due to government regulations, Deodar trees are no longer cut down, so newer houses are primarily built from cement instead of wood. Deodar trees can live for 500 to 600 years, and their majestic presence is common along the roads in lower Himachal.

In a village family, each member has a specific role that they are entirely responsible for. For instance, if one person is in charge of making rotis, it is their duty to prepare them for the entire family. Similarly, if someone takes care of the cows, that task is solely theirs. Duties are clearly defined and fixed in village life.

Villagers with apple orchards remain relatively inactive during the three winter months. They relax and enjoy this period, as everything they need for these months is stocked up at home.

The culture

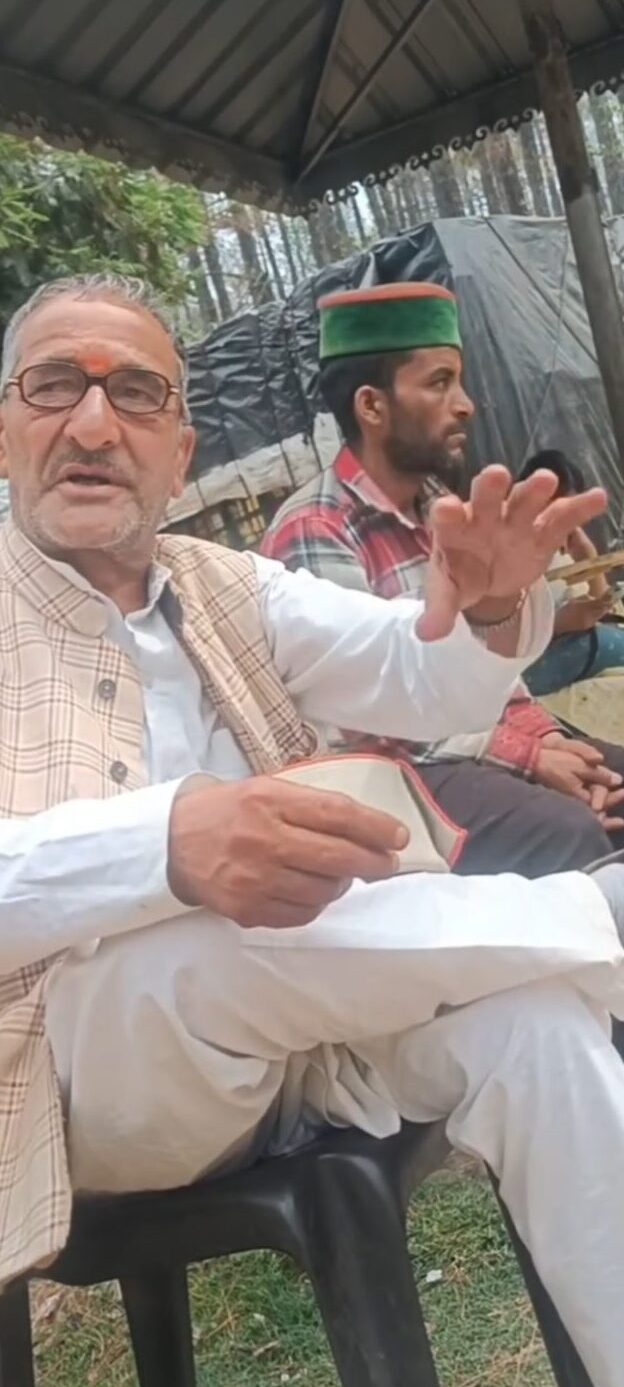

Clothing in lower Himachal is distinct from the rest of Himachal and Uttarakhand. People typically wear long kurtas paired with small jackets and traditional hats.

In Himachal, guests are truly treated as gods. Unlike in other places where people are judged by their character and achievements, in Himachal, individuals are valued without consideration of their accomplishments. Many locals who helped me didn’t even ask where I was coming from. There is a noticeable lack of formalities, and people are very accepting and flexible, with no rigid rules to follow.

There is also a Punjabi influence near the Punjab border. Before 1948, Himachal was mostly part of Punjab, and remnants of this influence can still be seen in places like Una district. Additionally, I noticed that people in lower Himachal frequently use the curse word “Beh***od” quite a lot.

In lower Himachal, each land is believed to have its own bhumi devatas, or family deities, known as kula devtas. For instance, Jamdagni Rishi is the deity of the Kullu district, where decisions are made. The word of the Devta Maharaj is considered final in all matters, often holding more sway than the government in land-related issues.

Issue with drugs

The moment I entered Himachal, I heard about drugs coming in from various states, including Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh. Charas has become commonly used, and I frequently saw people drinking the local alcoholic beverage, “kacchi.” Locals mentioned that the crime rate has been increasing due to drug use. In Malokhar, a grandmother and grandfather were recently killed by youngsters seeking money for drugs.

Drugs are a significant issue in Kullu and Manali, with people from all over the country visiting places like Manali and Malana specifically to smoke charas and experiment with other drugs.

Other aspects

Lower Himachal is growing rapidly due to higher education levels and profitable cash cropping. However, this growth is causing natural water sources, known as shrods, to dry up—something I didn’t observe in Uttarakhand. Additionally, there are no proper disposal plants in the area. People, accustomed to burning natural materials, also burn plastic to keep the area clean, but this practice is harmful. The government seems to be neglecting proper waste disposal measures.

Fortunately, tourism in lower Himachal is minimal, with mostly local HP-registered vehicles and only a few from Punjab and Haryana. This limited tourism has helped preserve much of lower Himachal’s natural beauty.

KINNAUR AND LAHAUL (Middle and upper Himachal)

The lifestyle

Life in Kinnaur and Lahaul/Spiti is significantly harder compared to the lower regions of Himachal. Despite the presence of cash crops like potatoes and peas, the harsh conditions, lack of proper transportation, and rocky terrain make life challenging. Similar to Uttarakhand, horses and mules are commonly used to transport goods due to the scarcity of roads and transport facilities.

While Nepali workers can be found in the uppermost parts of Lahaul, the lower regions of Kinnaur and Spiti lack workers from other areas. Tourism plays a crucial role in sustaining these regions, despite the difficulties faced by the local population.

The culture

In Kinnaur and Lahaul/Spiti, the dialects spoken are distinct from the rest of Himachal, where Pahadi Hindi and various dialects are prevalent across all 12 districts. In the lower half of Kinnaur, polygamy is practiced, where men marry multiple wives without societal taboo, believing it enhances their power, although this tradition is gradually evolving among the younger generation.

Unlike other parts of the country where young people often stay away from home during work and festivities, in Kinnaur, community events are integral, and non-participation can lead to social ostracization. Weddings here are elaborate affairs, drawing villagers together for collective celebrations.

The people of Kinnaur and Spiti/Lahaul identify themselves as tribals of Kshatriya lineage, fostering a strong caste identity, with Kinnaur exhibiting notably high levels of casteism within Himachal Pradesh. For instance, in Malana, within the Kullu district, locals consider themselves descendants of the Aryan race, maintaining strict traditions that prohibit outsiders from touching them or their belongings. Transactions are conducted by placing money on a stone and receiving goods in return.

These communities have a meat-eating tradition, influenced by their belief as descendants of Vanasur the demon, and they consume alcohol regularly, even offering it to their deities. While lower Kinnaur residents consume goat and chicken, those in upper Spiti also include yak in their diet.

Religiously, Kinnaur residents practice both Hinduism and Buddhism concurrently, often bearing names associated with both religions. Moving towards Spiti, Buddhism becomes more dominant, significantly shaping their customs and rituals. Their cultural practices diverge from mainstream Hindu customs, employing unique customs such as making garlands with fruits instead of flowers, and lacking the concept of Mangal Sutra.

Historically, their culture has been influenced by Tibetan traditions due to ancient trade routes, predating British road construction between 1850 and the 1930s. Trade included significant imports like Himalayan salt from Tibet, fostering a close relationship between Kinnauri tribes and Tibetans, who exchanged goods such as sheep, horses, butter, and gold.

Even into 2020, barter trade persisted between Shipkey, where the Satluj River enters Tibet, and Kinnauri people, though COVID-19 disrupted this route. Historically, Tibetans aided Kinnauri people against Mughal invasions, commemorated annually through the Lavi festival in Rampur Basher.

Similar to lower Himachal, Kinnaur operates under the governance of local deities called Shu, distinct from those in lower regions, each with their own myths and legends akin to Bon Buddhist practices, emphasizing animism and the belief in spirits within inanimate objects. The land here is not considered government property but rather belonging to these deities, maintaining unique cultural and spiritual traditions.

Way of life

In Kinnaur, the lower regions receive rainfall, whereas the upper parts, extending all the way to Ladakh, remain rainless throughout the year. Consequently, houses in the lower Kinnaur are constructed from wood, showcasing remarkable architectural craftsmanship with an interlocking system instead of nails. In contrast, houses in the upper regions are built with mud. The houses built in lower Kinnaur use Chilgosa pine wood rather than Deodar trees found in the lower parts of Himachal.

Similar to the southern regions, the government restricts tree cutting to two per family every ten years to preserve cultural and environmental balance. During the 1985 earthquake, Lahaul and Spiti reported 45 casualties, while Kinnaur, with its resilient wooden architecture, reported none. In the 2013 snow and flooding disaster that affected northern India, sheep—a vital livelihood source—perished, setting back the entire region by years. Even now, firewood from trees felled during that calamity continues to be used.

Water scarcity in the dry upper Kinnaur often sparks disputes over water sharing among locals, underscoring the critical importance of this resource in the region’s harsh climate.

Kinnauris and Spiti people, predominantly tribal, often face discrimination from the rest of Himachal Pradesh. Education for children in these regions is limited, typically taking place in monasteries where families pay approximately 25,000 rupees annually. Alongside standard education, children learn the local Boti language and Tibetan scriptures. It’s customary for each family to have at least one child who becomes a monk, although in recent years, the number of monks has significantly declined, leading to concerns about the erosion of cultural traditions over time.

In Kinnaur, sheep rearers are known for their exceptional hard work. Every year during the monsoon, cattle rearers from Mandi district and lower Himachal transport hundreds, sometimes up to 500 sheep, to the arid regions of upper Spiti where grazing is abundant. This journey spans 500 to 800 kilometers over hills, lasting 15 to 25 days without losing a single animal. These dedicated herders sleep on the mountainsides, demonstrating an intimate connection with their terrain. While once abundant, locals note a decline in cattle numbers over time.

To support these traditional livelihoods, the government has granted full access for cattle grazing across upper Himachal, ensuring continued pastoral practices in these remote regions.

Unreal climatic changes with insensitive tourists

The disparity in development between the highly developed Chinese side and India’s response through initiatives like the Vibrant Village project, aimed at rapidly improving roads to boost tourism, underscores the strategic and political dimensions of tourism in Kinnaur and Spiti/Lahaul. Despite a robust media presence, local residents in Kinnaur are vocal about firsthand experiences of climate change, expressing concerns that the region may become uninhabitable due to drastic reductions in snowfall. They criticize the government’s prioritization of infrastructure and tourism over environmental conservation.

In Kinnaur, hydrothermal electricity projects have proliferated to meet the energy demands of Punjab and Haryana, albeit at the cost of local ecosystems. Despite free electricity provisions for locals, flora and fauna are rapidly declining, exacerbated by reduced river volumes due to extensive pipeline systems. Drilling machines (“boomers”) have sensitized the landscape, leading to increased landslides, notably affecting the Sutlej River, which has seen a significant decrease in water volume.

Construction activities have led to heightened dust levels and unprecedented temperature rises, particularly detrimental in Chitkool, the final village in lower Kinnaur, which has lost its charm to uncontrolled tourism. During peak travel months from May to August, daily tourist arrivals often outnumber local residents, transforming village dynamics.

While tourism thrives, the Himachal Pradesh government faces financial losses, exemplified by foreign involvement in infrastructure tenders and funding for geothermal and dairy projects. Many tourists, unaware of the environmental degradation, rent bikes and contribute unwittingly to the region’s deterioration.

Local perspectives vary: while acknowledging developmental benefits such as improved lifestyles through tourism, cash crop farming, and hydroelectricity, many lament the irreversible ecological costs. They argue that tourism has inadvertently safeguarded Kinnaur and Spiti from becoming easy targets for geopolitical interests like China.

In response to tourism influxes, the government has enacted legislative measures such as the Marriage Act, Land Acquisition Act, and Paisa Act to safeguard local land rights. Despite these efforts, three primary tourist archetypes emerge: luxury-seekers focused on social media documentation in popular hubs like Manali and Shimla, clueless travelers dependent on locals for itinerary advice, and budget tourists traveling in groups to tick destinations off their lists.

Reflecting on my extensive travels across Himachal Pradesh over a month, the diverse landscapes and cultural richness akin to crossing multiple states have left a lasting impression. I encourage further exploration and discussion to deepen understanding of this complex and evolving region. If you found this account insightful, I invite you to explore related articles for a broader perspective.

I am a 31 year young PhD graduate who has decided to travel the length and breadth of India on my cycle, to document the journey of meeting a vast array of people. In my journey, I intend to understand the characteristic features of the people of this nation and categorize them based on their demographics, age, profession, gender, traditions, and cultural differences.