Read this before travelling North East India

The Northeast of India remains one of the least explored yet most diverse regions of the country. Despite covering just 8% of India’s land area, its cultural, geographical, and ethnic diversity rivals—or even surpasses—the rest of the nation. From towering Himalayan landscapes to lush valleys and vast plains, the region defies any attempt to generalize it under the label of the “Seven Sisters.” Even within individual states, there exist striking differences in culture, traditions, and ways of life.

The Northeast is home to a multitude of tribes, each with its own distinct identity, traditions, and aspirations. This diversity has also led to complex socio-political dynamics, with various groups advocating for autonomy and recognition. The presence of insurgent movements reflects the deep-rooted desire of different ethnic communities to preserve their heritage and assert their unique identities.

For travelers, the Northeast offers far more than just scenic beauty. It is a land of rich traditions, adventurous landscapes, soulful experiences, and culinary delights. Exploring the region is not just about visiting places; it’s about immersing oneself in a way of life that is deeply connected to nature and history. Standing amidst the towering Himalayan ranges, witnessing the resilience of tribal communities, and experiencing the simplicity of life here can be truly transformative.

My journey through the Northeast has left a lasting impact on me. Though I have only scratched the surface, covering less than 10% of what this incredible region has to offer, I hope to share my insights and experiences through this article. I have also included Sikkim, as it naturally aligns with the region in terms of geography and culture. While I have made every effort to present an unbiased perspective, my experiences are inevitably shaped by my mode of travel and personal outlook. I welcome you to engage, share your thoughts, and contribute to the discussion in the comments section.

ASSAM

Famous for its vast tea estates and one of the world’s largest rivers, the Brahmaputra, Assam offers a rich experience for nature and culture enthusiasts alike. The state is home to several national parks, including Kaziranga and Manas, which shelter rare wildlife such as the one-horned rhinoceros. Culturally, Assam thrives with its vibrant traditions, including Bihu, a lively dance form, and other artistic expressions dating back to the 16th century.

However, Assam also faces significant challenges. Illegal immigration from neighboring Bangladesh has been a long-standing issue, impacting demographics and socio-political dynamics. Despite its natural wealth, Assam remains one of India’s poorer states, with a lower quality of life for many of its residents. The state’s economy is primarily driven by agriculture, supplemented by petroleum and natural gas industries. Assam’s climate is characterized by heavy and persistent rainfall, influencing its unique architectural styles, where homes are often elevated to withstand flooding.

Demographics

Assam can be geographically divided into three regions: Upper Assam, Central Assam, and Lower Assam. Upper Assam stretches from the easternmost part of the state to Tezpur, Central Assam lies between Guwahati and Tezpur, and Lower Assam extends from West Bengal to Guwahati.

While Assamese is the predominant language spoken across the state, the Barak Valley in the southern part of Central Assam has a significant Bengali-speaking population. Approximately 50% of the state’s residents speak Assamese, while 30% speak Bengali, with the remaining population speaking various tribal languages. The major tribes of Assam include the Bodo, Miri, and Karbi, along with several smaller tribal communities, collectively making up around 12% of the state’s population.

Religion and immigration

Hinduism is the dominant religion in Assam, followed by around 60% of the population. Most Assamese Hindus belong to the Ekasarana sect of Vaishnavism, which was widely practiced during the Ahom rule that lasted nearly 600 years. This Neo-Vaishnavite movement was led by the 15th–16th century saint Srimanta Shankardeva, who, along with his disciples, established Satras—monastic institutions that became centers of cultural and religious learning across the state.

The influence of this movement is especially evident in Majuli, the cultural heart of Assam. This river island, one of the largest in the world, is home to some of the most significant Satras, preserving the rich traditions of Assamese Vaishnavism to this day.

Around 35% of Assam’s population follows Islam, with 11 out of 32 districts having a Muslim majority. This demographic shift is largely attributed to the significant influx of Bengali migrants from neighboring Bangladesh. A century ago, Hindus made up nearly 80% of the state’s population, but their proportion has gradually declined due to this migration. Census data from the past decade indicates that Assam’s Muslim population has been growing at a rate of 5–7% per decade.

Quality of life

As one of the poorest states in India, Assam struggles with widespread poverty and high unemployment, leading many to migrate to neighboring northeastern states in search of work. Assamese laborers can be found across the Seven Sister states, working in various sectors. Apart from a few developed cities like Guwahati, Tezpur, Jorhat, Dibrugarh, and Sivasagar, much of the state remains underdeveloped. In rural areas, it’s common to see people commuting on old bicycles, reminiscent of scenes in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Education and healthcare facilities are lacking across the state, contributing to Assam having one of the highest infant mortality rates in the country. During my travels, I noticed a high prevalence of tobacco consumption, with even women frequently chewing tobacco. Alcohol consumption is also widespread, particularly among the Boro tribe, who are permitted to live in forest areas and produce large quantities of rice-based fermented alcohol, which they sell locally.

Culture

One of the most striking cultural aspects of Assam is the widespread habit of chewing betel nut. It is deeply ingrained in daily life, to the extent that offering betel nut to guests is considered more customary than serving water or food. During my travels, I often felt as if someone walking beside me might spit at any moment—a reflection of just how prevalent this practice is. Having traveled extensively across northern India, I found that the tradition of chewing paan and tobacco reaches its peak in Assam, where it seems almost inescapable.

Much of Assam’s cultural identity revolves around the Bihu festival, which is deeply tied to the state’s agricultural roots. Given Assam’s fertile lands, nourished by the mighty Brahmaputra River, Bihu is celebrated in sync with the changing seasons that influence harvest cycles. Dating back to around 3500 BC, it is one of the oldest festivals in India.

The Bihu dance, a vibrant expression of fertility and passion, brings together young men and women who perform rhythmic movements to the beats of traditional drums. Beyond dance, Assam’s cultural essence is reflected in its attire. Women don the elegant Mekhela Chador, while the Japi (a traditional bamboo hat) and the Gamosa (a handwoven cloth, primarily crafted by the Mishing tribe) further enhance the distinct and colorful heritage of the state.

As a vegetarian, I couldn’t fully experience Assam’s diverse culinary offerings, especially its famed fish dishes sourced from the mighty Brahmaputra River. However, I did get a taste of the traditional Assamese thali, which was a delightful experience. A highlight of the meal was *Pitika*—a simple yet flavorful mashed potato dish, often accompanied by mustard oil and green chilies.

Assamese cuisine is centered around fresh, locally sourced ingredients, with a variety of vegetables cooked to perfection and served alongside rice and fish, creating a wholesome and satisfying meal for those who enjoy rich flavors. Another unmissable aspect of Assamese food culture is its tea, typically served without milk, allowing its distinct aroma and natural flavors to shine.

Assam is moderately prone to earthquakes and highly vulnerable to floods, which significantly influences its traditional architecture. Every year, countless homes along the Brahmaputra River’s banks are lost to flooding, necessitating construction methods that enhance resilience.

During my travels, I noticed that houses in Assam are often built with a combination of concrete and mud. This design ensures that even if an earthquake damages the structure, only part of the house is affected. Sal tree pillars, known for their resistance to insects, provide sturdy support, while jute sticks and mud serve as an effective adhesive for ceilings and walls, offering excellent heat insulation. Additionally, lightweight materials help prevent severe collapses during earthquakes. Given Assam’s heavy monsoon rains, rooftops are typically made of tin sheets to withstand prolonged downpours.

In tribal areas, the construction style differs slightly. Houses are primarily built using bamboo and are elevated on stilts. This elevated design serves multiple purposes: it prevents floodwaters from entering the living space, allows for proper ventilation, and provides an area underneath for storing firewood and rearing livestock such as chickens, protecting them from predators like hawks. This ingenious adaptation to the region’s climate and geography reflects the deep-rooted wisdom of Assam’s indigenous communities.

My journey through Assam was a mix of experiences—good, bad, surprising, and at times, even strange—yet undeniably enjoyable in its own way. One of the challenges I faced as a traveler was the language barrier, as most signboards and public writings are in Assamese, making navigation tricky for those who only speak Hindi or English.

If you’re planning a visit to Assam, there are a few must-see places. The **Majuli Islands**, the cultural heart of the state, offer a glimpse into Assam’s unique heritage and traditional way of life. The **Kaziranga National Park**, home to the iconic one-horned rhinoceros, is an unforgettable experience for wildlife enthusiasts. And of course, don’t miss out on trying the **Assamese thali**, a flavorful meal that truly captures the essence of the local cuisine.

ARUNACHAL PRADESH

Arunachal Pradesh, with its breathtaking Himalayan landscapes, is often recognized for its popular tourist destinations like Tawang, Mechuka, and Dong Valley. However, beyond its scenic beauty, it is one of the most ethnically diverse states in India. Home to over 26 major tribal groups, each with its own language, traditions, and customs, Arunachal Pradesh stands out as a cultural mosaic. The state’s religious landscape is equally diverse, with Buddhism prevalent in the western region, animism (locally known as Donyi-Polo) followed across much of the state, and a significant portion of the population having converted to Christianity in recent times. While the growing Christian influence has been a topic of discussion, many locals still practice their ancestral traditions, blending ancient customs with modern development. With a population density of just 17 people per square kilometer, it remains one of the least populated states in India, offering a rare glimpse into a way of life that balances tradition and progress.

Demographics

Arunachal Pradesh can be broadly divided into three regions—western, central, and eastern—each home to distinct ethnic tribes with varying religious beliefs. In the western region, the Monpa tribe, predominantly Buddhist, resides. The central region is home to the Thani clans, which include the Apatani, Nyishi, Adi, Galo, and Tagin tribes, following the indigenous Donyi-Polo faith, with a growing number converting to Christianity. The eastern region is primarily inhabited by the Tirap, Longding, and Changlang (TLC) tribes, such as the Nocte, Tangsa, Wancho, and Singpho, most of whom are Christians. Among these, the Nyishi tribe is the largest in population. The tribes of Tirap and Longding share close ethnic ties with the Nagas of Nagaland, leading to demands for integration and subsequent militancy in the eastern region.

Each tribal group speaks its own language, with 26 major tribal groups further divided into numerous sub-tribes. Most tribes settle in villages named after their ancestors, a tradition that helps maintain lineage and avoid inbreeding—except for the Apatani, who follow a different practice.

Interestingly, Arunachal Pradesh was never colonized by the British, and Christian influence arrived in the region relatively late. Between 2001 and 2011 alone, the Christian population grew from 15% to 30%, with estimates suggesting an increase of over 10% per decade. Religious perspectives vary across tribes. Followers of Donyi-Polo, an animistic faith that worships the sun, moon, and nature, claim they coexist peacefully with other religions. However, some Christian groups consider Donyi-Polo practices to be linked with black magic and evil spirits, leading to social divisions. Despite these differences, many locals seem to embrace religious diversity. It is not uncommon to find families where members follow different faiths, reflecting a unique blend of tradition and change. Throughout my travels, I observed distinct cultural attributes among these tribes, which I have explored in a separate section of this article.

The culture

From my travels across India, I’ve observed that alcohol is deeply integrated into tribal cultures, and Arunachal Pradesh is no exception. Rice beer is widely consumed across the state, with almost every household fermenting rice to produce their own brew. In addition to being a popular drink, fermented rice itself is a dietary staple, believed to provide essential carbohydrates and help keep the body warm in the cold climate. In earlier generations, it was common for people to drink rice beer throughout the day, with some even relying on it as a primary source of sustenance.

The followers of the Donipolo tradition still uphold their ancient customs, including the role of the shaman. In times of unexplained misfortune within a family, a shaman is called upon to act as a bridge between the spirit world and the people. The shaman determines what the spirits require, often prescribing a ritual sacrifice to restore balance and fulfill the necessary conditions for resolving the issue.

Each tribal group in Arunachal Pradesh has its own distinct history, with ancestral lineage playing a significant role in their identity. Many tribes name their villages after their forebears, reinforcing their connection to their heritage. This tradition also influences marriage customs, as it helps regulate unions within the community. Folklore is deeply embedded in these tribes, shaping their cultural practices. One such legend comes from the Apatani tribe, primarily found in the central region. Historically, Apatani women were renowned for their beauty, which led to frequent kidnappings by invaders. To protect themselves, the women began tattooing their faces to appear less attractive, a practice that persisted for generations as a means of safeguarding their community.

Dowry is not a part of marriage traditions in Arunachal Pradesh. Instead, the groom presents Mithuns—a rare bovine species native to the region—to the bride’s family as a token of respect and goodwill. The number of Mithuns offered is seen as a symbol of the groom’s wealth and social standing, with those able to give more being regarded as more prosperous.

The cuisine of Arunachal Pradesh is distinct from the rest of India, as it primarily consists of simple, boiled food with little to no spices. Meat plays a dominant role in their diet, with country fowl, pork, Mithun, and yak (in the western regions) being staples, along with other animals hunted locally. A common practice in most households is to store dried meat above the central firewood hearth in the hallway. Pork, in particular, is often seen hanging beside the firewood, slowly drying over time. Each evening, the meat is reheated directly over the fire before being consumed. For breakfast and lunch, people typically eat plain rice, often in porridge form, accompanied by lal chai (green tea) or sugar. The same dried meat is also eaten alongside rice during meals.

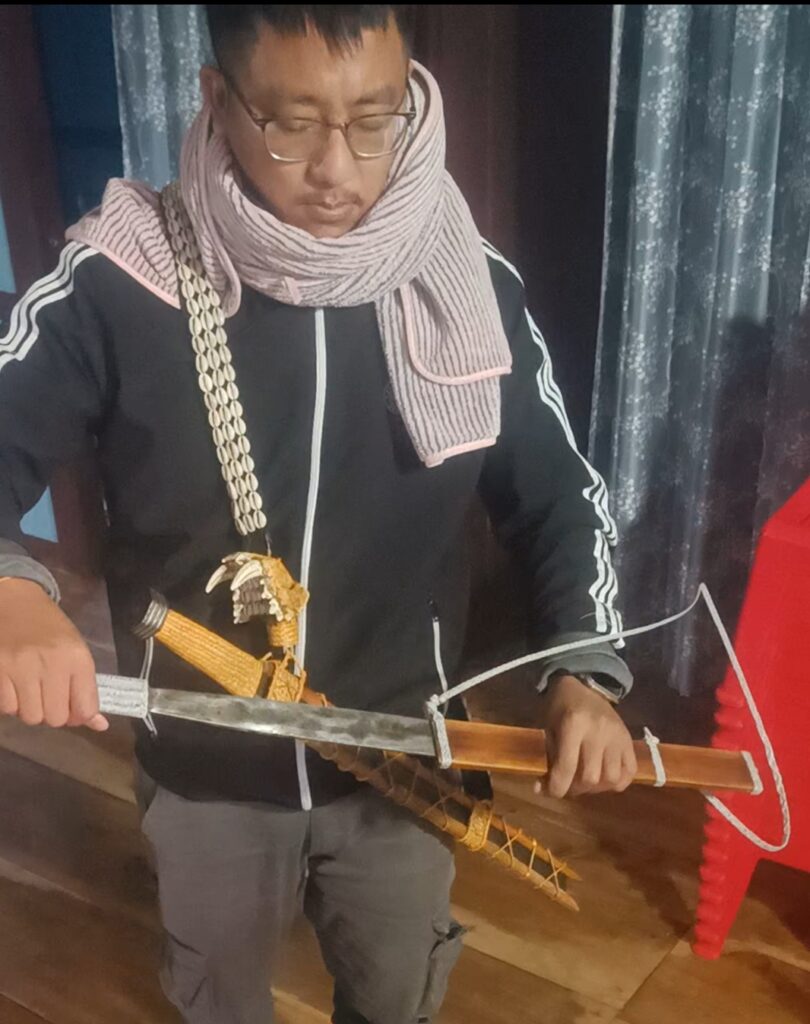

Travelers in Arunachal Pradesh will often notice locals carrying a knife, dagger, or small sword slung in front of them in a pouch. These tools are essential for their daily lives, used for clearing overgrown plants and weeds while navigating forests, hunting, and even for self-defense in ancestral times. It’s also not uncommon to see some locals carrying shotguns or air guns on their backs, reflecting the deep-rooted hunting culture that still thrives in the region.

The traditional houses built by Arunachal Pradesh’s tribal communities showcase remarkable craftsmanship, with bamboo intricately woven to form the walls. The flooring is made from sturdy wooden logs sourced from the dense forests, while tin sheets are commonly used for roofing. In older tribal homes, even everyday items like stools, carpets, and some kitchen utensils are crafted from bamboo. One of the most fascinating aspects of tribal architecture is the community-driven construction process—when a house is to be built, the entire village comes together to assist, often completing the structure in as little as three days. The wood used for construction is sourced from forests owned collectively by the villagers, reinforcing their deep connection to nature and communal way of life.

Quality of life

Despite hearing that excessive drinking is a leading cause of mortality among the tribals, I was surprised to find that many people in Arunachal Pradesh live long lives despite their drinking habits. This could be attributed to the clean air and pure water provided by the lush Himalayan landscape. Interestingly, Arunachal is one of the few places in India where the government does not own the land—the locals do. Every mountain range, as far as the eye can see, belongs to the people. However, the government has urged residents to occupy as much land as possible before official fencing is carried out, after which any unclaimed land will be taken over by the state. Despite the vast land holdings, disputes over property are rare, possibly due to the sheer abundance of natural resources, which ensures that everyone has enough.

Much of the land owned by the locals remains unoccupied or uncultivated, as they believe it should be preserved for future generations. On the small portions they do cultivate, they grow rice, oranges, kiwis, and bananas—entirely organically, having learned from the harmful effects of pesticides and insecticides in the past.

Development in Arunachal Pradesh has been relatively recent. National highways with double lanes were laid as recently as 2021. Even along these highways, electricity was unavailable until 2015, forcing people to retire early in winter as darkness sets in quickly in the easternmost parts of India. Gas cylinders only became widely accessible around 2017. Just two decades ago, even in settlements along the highways, packaged biscuits were considered a luxury.

People

It is difficult to categorize the people of Arunachal Pradesh into a single identity, as each tribal group has its own distinct religion, customs, traditions, attitudes, and behaviors. During my journey, I noticed a striking contrast in personalities—some locals were initially reserved but turned out to be incredibly warm once the conversation progressed, while others spoke in a more assertive tone, appearing rough in their demeanor and gestures.

A noticeable aspect of life in Arunachal is the contrast between material possessions and living conditions. Many people, even in remote regions, own high-end vehicles despite residing in modest bamboo houses. Locals shared that this is largely due to heavy payouts by politicians during elections, with some individuals receiving as much as 3–4 lakh rupees. Additionally, with substantial government funding allocated for rural development, many have become contractors, leading to unexpected wealth even in isolated villages.

Despite being tribal and engaging in hunting, the people of Arunachal Pradesh have a deep-rooted respect for nature. Their traditional beliefs teach them to live in harmony with their surroundings, fearing that nature’s spirits will punish excessive exploitation. Their indigenous knowledge regulates hunting practices—certain animals are hunted only in specific seasons and in controlled numbers. For instance, during the Shravan season, when most animals mate, they refrain from hunting and fishing. They also understand the reproductive cycles of different species, avoiding hunting deer, which only produce one offspring a year, while allowing more hunting of species like Juin, which reproduce in large numbers.

However, some locals expressed concern that commercialization is disrupting this balance. Increasingly, animals are being hunted indiscriminately for profit, putting traditional conservation practices at risk.

My journey through Arunachal Pradesh was an unforgettable experience, one that will stay with me for a long time. Unlike many other parts of the world, I found that people here do not engage in conflicts over religion or land. However, my travels did raise questions about the increasing conversion to Christianity—some believed it had erased the tribal instincts of the people, while others felt it had led to the loss of indigenous cultures and traditions. Regardless of these debates, the rich diversity of customs and traditions in Arunachal Pradesh is something truly unique and worth cherishing.

NAGALAND

Nagaland shares many similarities with Arunachal Pradesh, particularly in its low population density. It is one of India’s least populated states, with only Goa and Arunachal Pradesh having fewer inhabitants. The state is home to 17 major tribes spread across 16 administrative districts, each with its own distinct customs and languages, making Nagaland one of the most culturally diverse regions in the country.

Known as the “Land of Folklore,” Nagaland’s history has largely been passed down through oral traditions, with the earliest Naga settlements dating back to the 13th century. Agriculture remains the backbone of its economy, with rice cultivated as the staple crop on nearly 80% of the farmland. Cardamom, tea, and coffee are grown in the hilly regions, though traditional slash-and-burn farming methods continue to hinder agricultural efficiency. The state is also rich in mineral resources such as iron, nickel, cobalt, chromium, and marble, though these remain largely untapped.

Historically, the Nagas fiercely resisted British rule, particularly when the British sought to expand their influence over Assam’s tea estates. However, by the 19th century, Christian missionaries from the United States and Europe had successfully converted the region’s animistic tribes, leading to a present-day Christian majority of 87%. Due to this widespread conversion, Nagaland is now recognized as the only predominantly Baptist state in the world. The state boasts a high literacy rate of 80%, with English widely spoken among its people.

Culturally, Nagaland is known as the “Land of Festivals,” with year-round celebrations reflecting its vibrant heritage. The Naga people have a deep appreciation for colors, which is evident in the intricately woven shawls made by local women. They also craft jewelry from a variety of natural and animal materials, including glass, shells, stones, teeth, claws, horns, metals, and bones. Unlike the boiled food culture of Arunachal Pradesh, Naga cuisine is rich in smoked and fermented flavors. Traditional folk songs and dances, characterized by rhythmic group movements and the sounds of indigenous musical instruments such as bamboo mouth organs, bamboo flutes, and cattle-skin drums, form an essential part of Naga culture.

Culture

One of the most striking aspects of Nagaland is its distinctly Westernized culture. While the ancestors of the region once followed an animistic faith called Lichapa, today, over 95% of the population identifies as Christian. Every village, no matter how remote, has at least three churches, while religious sites from other faiths are almost nonexistent. Similar to Arunachal Pradesh, vast forest lands in Nagaland are owned by local communities rather than individuals, with the belief that they should be preserved and passed down to future generations. The villages are named after their ancestors, a tradition that helps prevent inbreeding within tribal communities.

Nagaland’s transport system, however, leaves much to be desired. The roads are in poor condition, making travel difficult. Despite this, the state maintains an impressive standard of cleanliness, even in its most remote villages. Throughout my journey, I saw waste bins systematically placed and segregated into plastic and organic waste, a rare sight in many parts of India. Public restrooms are available in nearly every town, city, and village, and they are remarkably well-maintained.

Culturally, Nagaland is far more modernized than other tribal-dominated states. Western clothing is the norm, and English is widely spoken, especially among the youth. Education is highly valued, with numerous Christian missionary schools and colleges playing a significant role in shaping the younger generation. English is more commonly spoken here than Hindi, making communication easier for travelers familiar with the language.

Though Nagaland is known as the “Land of Festivals,” many of its traditional celebrations have taken on a modern twist. The festivals, while rooted in tribal heritage, now seem more like cultural showcases for the outside world rather than deeply ingrained community traditions. A prime example of this is the Hornbill Festival, which, though vibrant and widely celebrated, feels more like a performance than an authentic tribal gathering.

Governance

Many Nagas hold a strong separatist sentiment, seeking autonomy from India and resisting central government interference. With the Assam Rifles stationed in Nagaland due to its border with Myanmar, there is deep-seated resentment toward the Indian Army. Locals largely reject external governance, and underground anti-nationalist groups like the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) wield significant influence. The NSCN factions, including NSCN (IM) and NSCN (K), are classified as terrorist organizations by the Indian government but continue to dictate many aspects of life in the state.

One striking example of their influence is the strict enforcement of Sunday as a holy day of rest. All shops, stores, and restaurants remain completely shut across Nagaland in observance of the Sabbath, making it impossible to find even basic necessities like bottled water. During winter, when darkness falls early—around 5 PM—businesses close even earlier. With limited street lighting, even the cities feel deserted after sundown.

Firearms are a common sight in Nagaland, with people openly carrying rifles and guns without any intervention from law enforcement. Gun shops operate freely in major cities, selling and servicing firearms for the public. Despite this, crime levels remain relatively low, possibly due to the deep-rooted tribal codes of conduct and internal governance.

Nagaland faces significant economic challenges due to a lack of industries, resources, and job opportunities. A large portion of the population remains unemployed and depends on central government funds for survival. These funds, meant for state development, are distributed through village head representatives, often leading to corruption and mismanagement.

Agriculture is surprisingly minimal in Nagaland, with most essential commodities, including rice, being imported from Assam. Despite this, an interesting business community has emerged—many Rajasthani Marwaris have settled in the state, running general stores and supplying essential goods in towns and cities.

People

From my observations, Nagas tend to have a strong and assertive demeanor, though attitudes and mannerisms vary across the different tribal groups. Historically, they were fierce headhunters, known for their resilience in resisting British forces. This warrior spirit still lingers, with many Nagas deeply committed to their beliefs and willing to fight for them. However, some locals claim that the widespread conversion to Christianity has softened their traditionally aggressive nature, making them more accepting and peaceful.

While I didn’t personally encounter any hostile incidents, I heard several accounts of gangs stopping people on the roads and demanding ransom. Even the army personnel I spoke with admitted they tread carefully to avoid provoking the locals. The atmosphere carries an underlying tension, which seems to stem from the region’s long history of conflict and separatist sentiments.

When it comes to food, Nagas eat almost anything—whether it flies, crawls, creeps, walks, or swims. Dog meat is considered a delicacy, and vegetarian food is often fermented, such as banana flowers and beans, which can be challenging for outsiders to consume. Given their diverse meat consumption, I got the impression that animal welfare is not a major concern here. I frequently saw locals using catapults to pelt street animals, which seemed to reflect a deep-seated hunting instinct.

Despite modernization and religious transformation, the tribal temperament is still evident. Even minor disagreements can escalate quickly into heated confrontations. I personally witnessed multiple fights breaking out over seemingly trivial issues, reinforcing the impression that Nagas have a natural inclination for confrontation.

MANIPUR

Manipur is a land of diverse ethnic communities, with the Kuki and Naga tribes residing in the surrounding hills and the Meitei people inhabiting the plains. The official language is Meitei (Manipuri), though the Kuki tribes are further divided into multiple clans, each with its own distinct language. Religious demographics are also split along geographical lines, with the hill tribes predominantly Christian and the Meitei people in the plains following Hinduism or Christianity. Over the last 50 years, the Hindu population has declined from 60% to 40%, while Christianity has risen from 15% to 40%. Unlike Nagaland, where Christianity has nearly replaced indigenous beliefs, Manipur has retained a small but significant population of Sanamahists who follow the animistic traditions of their ancestors and worship their household deity, Lainingthou Sanamahi.

Similar to Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland, Manipur is among India’s least populated states, ranking 23rd out of 28. The population is roughly split, with Meiteis making up about 50% and the rest almost equally divided between Nagas and Kuki-Zo tribes. Interestingly, Manipur is credited with introducing the sport of polo to Europeans.

However, the state has a long history of insurgency and ethnic violence. Armed opposition groups such as the United National Liberation Front (UNLF) and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) have been active since the 1960s, engaging in conflicts with the government. Despite repeated pleas from the state authorities, the central government has largely failed to address these issues, leading to the imposition of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). This law grants the military sweeping powers, including the ability to detain individuals for 24 hours without a warrant, fueling further protests and unrest.

In recent times, ethnic clashes between the Meitei and Kuki communities have drawn international attention, resulting in hundreds of deaths and the displacement of thousands from their homes. Over 100 churches and temples have been destroyed in the ongoing conflict. The instability has given rise to various insurgent groups with differing demands—some Meitei factions seek independence from India, Kuki insurgents demand a separate state, and Naga groups aim to merge the northern hill regions of Manipur with Nagaland.

Despite these conflicts, Manipur remains rich in natural resources, particularly its vast bamboo forests covering approximately 3,000 square kilometers. The state is also known for its diverse agricultural produce, including medicinal and commercial crops like plums, lychees, pears, cashews, walnuts, oranges, passion fruit, and pineapples. Notably, Manipur’s black rice has been granted a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, making it an exclusive regional product.

Culture

In Manipur, daily life follows the natural rhythm of the sun, with shops and stores shutting down by 5:30 PM and reopening as early as 5 AM. While the state is nearly as westernized as Nagaland, it lacks the same level of organization. Road conditions are poor, with ongoing construction making travel dusty and difficult. However, like in Nagaland, English is more widely spoken than Hindi.

Manipur boasts a rich cultural heritage, particularly in fashion, music, and the arts. The state places a strong emphasis on sports and is home to the only language in Northeast India with its own indigenous script, the Meitei Mayek, which has Tibeto-Burman origins. Even Assamese, in contrast, derives its script from Bengali. Manipur also has the most developed film industry in the Northeast. Bollywood films are outright banned in the state, and actors who participate in external film industries risk being blacklisted from Manipuri cinema.

Traditional arranged marriages are less common in Manipur, with love marriages being the norm. Interestingly, in cases where lovers struggle to meet due to family restrictions, the bride elopes with the groom, and the families are then expected to accept the union.

Women play a dominant role in Manipuri society, participating in all sectors of work and leading protests and social movements. Manipur is home to India’s only women-run market and one of the largest in the world—the iconic Ima Market in Imphal. This historic marketplace, run entirely by women, has been functioning for over 500 years and remains a symbol of female empowerment in the state.

From my observations, Imphal stands out as one of the few places in India where people maintain a truly balanced diet. While non-vegetarian food is a staple, vegetables also play a significant role in their meals. Like in Nagaland, many dishes incorporate fermentation, enhancing both flavor and nutritional value.

The locals have deep knowledge of medicinal herbs, consuming them as needed for their health benefits. Among Brahmin families, a tradition of offering fruits to God daily ensures a regular intake of fresh produce, contributing to a well-rounded diet. Additionally, customs such as starting a meal with boiled beans and vegetables provide essential dietary fiber, aiding digestion and promoting overall health.

History and heritage

The valley region of Imphal, where the Meiteis now reside, was once an uninhabitable marshland. Originally hill dwellers, the Meiteis gradually moved down as the valley dried up over time. The Kanglei Kingdom, which settled in Imphal, derived its name from “Kanglei Pak,” meaning “the first dry land.” Even today, the kingdom’s palace stands on what was the earliest patch of dry land in the valley.

The Loktak Lake, one of the largest freshwater lakes in Northeast India, is a remnant of this once-wet valley, which explains why Imphal remains flood-prone. The sacred Koubru Peak, revered by the Meiteis who once followed the Sanamahi religion, is now located in the Kangpokpi district, home to the Kukis. As the Meiteis moved to the valley, the Kukis, who migrated from Myanmar, settled in the surrounding hills.

While many Meiteis converted to Hinduism, a significant portion still follows the ancient Sanamahi religion, which, despite its similarities to Hinduism, maintains distinct differences. Sanamahi traditions are deeply rooted in tantric practices and Vastu Shastra, with a designated space in the southwest corner of homes for their deity, Lailingthou. It wasn’t until the 17th century that Vaishnavism was introduced by the ruling king, but in recent times, there has been a resurgence of interest in reviving the indigenous Sanamahi traditions.

Conflicts

Manipur was originally inhabited by the Meiteis in the valley and the Nagas, who primarily lived in the northern hill districts. The Meiteis and Nagas share cultural similarities and consider themselves descendants of the same ancestral lineage. However, the Nagas in Manipur have a distinct identity from those in Nagaland. Today, discussions about Manipur often center around Imphal and its Meitei population, while the complexities of its tribal communities are less acknowledged.

When the British arrived in the Northeast, they viewed the Nagas as a threat and brought the Kukis from Myanmar to counter them. Throughout the 1990s, violent conflicts between the Kukis and Nagas were common, though in recent years, tensions have shifted toward a Meitei-Kuki confrontation. Once stability was restored, the Meiteis allocated hilly regions—historically their ancestral land—to the Kukis for settlement. Now, the Kukis are demanding these territories as a separate state, which the Meiteis strongly oppose. The districts of Kangpokpi and Churachandpur are Kuki-dominated, but the Meiteis argue that Churachandpur was taken from them through violence rather than being granted. Additionally, while Kukis can purchase land in the plains, tribal laws prevent Meiteis from buying land in the hills, creating further discontent.

The Nagas have remained neutral in this conflict, reluctant to support the Meiteis since they were the ones who initially allowed the Kukis to settle. The Meiteis argue that the Kukis are not indigenous to Manipur and that their demand for a separate homeland is unjustified. The situation is further complicated by religion—since both the Nagas and Kukis were converted to Christianity by Western missionaries, the Kukis have leveraged their Christian identity to foster better relations with the Nagas. Some Meiteis claim that Hinduism historically viewed tribals as outside the caste system and thus “unholy,” which prevented mass conversions to Christianity. As a result, Christianity in Manipur has long been perceived by the valley Hindus as a “tribal religion.” The Meiteis, who traditionally enjoyed a more prosperous and structured way of life in the valley, feel this religious and cultural distinction plays a role in the ongoing divide.

However, the conflict extends beyond ethnic and territorial disputes. It is deeply tied to the illicit drug trade, which has led to it being labeled a “narco-terrorism war.” The funding for weapons and insurgent activities is allegedly fueled by money from drug cartels. Kukis, historically a nomadic tribe practicing Jhum cultivation—a slash-and-burn farming method—have now turned to poppy cultivation in the hills. Meiteis argue that this has caused significant environmental damage, unlike the Nagas, who have a strong emotional connection to their land. Allegations suggest that high-ranking political figures, including the Chief Minister’s son and even Amit Shah’s son, are involved in protecting the Kuki-run drug trade, further complicating efforts to resolve the crisis.

This has escalated into a complete division between the two communities. Not a single Kuki remains in Imphal, just as no Meitei lives in Kangpokpi. The violence has displaced thousands on both sides, forcing many into relief camps. While Meiteis claim that Kuki homes in Imphal remain untouched, they allege that Kukis have burned down Meitei homes in Kuki-dominated areas. A visit to one of the relief camps in Imphal shed light on the dire conditions faced by the displaced. Once self-sufficient individuals with land and livelihoods now find themselves trapped in a cycle of uncertainty and despair. Reports of suicides in these camps are not uncommon, as many struggle to cope with the loss of their homes, identity, and sense of purpose.

In the hills of Manipur, governance operates on local terms, with little regard for central authority or military control. Even army personnel stationed there must navigate the region cautiously, often deferring to local customs and power structures. The situation has created a stark contrast between the valley and the hills, leaving the Meiteis feeling isolated, as if trapped in a confined space. Many fear venturing beyond the valley, believing that stepping into the hills could cost them their lives.

During my journey toward Jiribam, near the Assam border, a local man shared his apprehension about traveling by road. He admitted that even when using public transport, such as buses, there was a lingering fear of being attacked. The deep-rooted tensions and history of violence make peace seem like an unattainable goal. The past continues to shape the present, with each community holding onto its traumas and narratives, making reconciliation incredibly difficult.

MIZORAM

With over 90% of its land covered in forests, Mizoram is the most heavily forested state in India. It is also the second least populated state, surpassed only by Sikkim. The majority of its inhabitants trace their origins to the Chin Hills of Myanmar and belong to the Mizo, or Zo, tribal community. Before British missionaries introduced Christianity, the Mizos followed an animistic faith known as the Sakuha religion.

Their lifestyle closely resembles that of the Kuki tribes of Manipur, who also descend from Myanmar. Both communities practice slash-and-burn agriculture, or Jhum cultivation, which continues to be a traditional farming method in the region. Like Nagaland, Mizoram is predominantly Christian, with nearly 90% of its population adhering to the faith. Despite being one of the most literate states in India, with a literacy rate exceeding 90%—second only to Kerala—over 20% of its population still lives below the poverty line.

Mizoram is also the most tribal-dominated state in India, with about 95% of its population belonging to various indigenous groups. Cultural celebrations revolve around traditional dances, and most festivals align with the agricultural cycle, particularly in March and April when fields are cleared for Jhum cultivation. Football is the most beloved sport in the state, with many Mizoram players making their mark at the national level.

Previously a part of Assam, Mizoram gained full statehood only in 1987, making it one of India’s youngest states.

Development

The lifeline of Mizoram, National Highway 6, which connects Silchar to Aizawl, is a narrow, single-lane road in a severely damaged state. Its poor condition reflects the region’s lack of infrastructure and development. Aizawl, the state’s most developed city, is home to nearly one-third of Mizoram’s population, all of whom rely heavily on this road for transportation and supply chains.

The practice of Jhum cultivation and the widespread use of makeshift tin-shed houses suggest that the local communities may have retained elements of their nomadic past. Despite the state’s rich natural resources, they remain largely underutilized, contributing to economic insufficiency and dependence on external support. A lack of exposure to modern agricultural and industrial techniques has further perpetuated poverty in the region.

Famine and the separation

In 1959, the Mautam famine struck Mizoram due to bamboo flowering, which led to a surge in the rat population, devastating crops. In response, the Mizo National Famine Front (MNFF) was formed, later evolving into the Mizo National Front (MNF).

Between 1955 and 1960, the MNF emerged as a separatist group demanding Mizoram’s independence from Assam. Declared an outlawed insurgent group in 1967 due to its militant actions, it continued its struggle until Mizoram was granted Union Territory status in 1971 and eventually achieved full statehood in 1987.

Culture

One of the defining aspects of Mizo culture is *Tlawmngaihna*, a deeply ingrained value that emphasizes hospitality, kindness, and selflessness.

Unlike other northeastern states, Hindi is rarely spoken in Mizoram. Due to the state’s strong Christian influence, English is widely used, much like in Nagaland. While businesses don’t shut as early as in Nagaland, Sundays see a complete closure of shops and establishments, reflecting the state’s predominantly Christian population. However, unlike Nagaland, Mizoram struggles with widespread poverty.

Since the Mizo language lacks its own script, everything is written using the English alphabet. Signboards and written communication are in Mizo but spelled in English. Linguistically, the language does not have plural forms, and formal honorifics are absent, with everyone being addressed in the singular form, reflecting a more egalitarian social structure.

Mizoram is a heavily meat-dominant state where food is primarily boiled, with minimal use of oil or spices. Nearly all restaurants serve only non-vegetarian dishes, with very few vegetarian options available. The most commonly found vegetables are cauliflower, potatoes, and beans. Pig farming is widespread, playing a significant role in their diet and economy.

The Mizo people have relatively few traditional musical instruments but a rich variety of dance forms, reflecting their deep cultural heritage. Their continued practice of *Jhum* (slash-and-burn) cultivation and reliance on traditional customs highlight the state’s strong tribal roots and connection to its past.

People

The people of Mizoram seemed honest and not driven by greed for money. They charged fair prices and did not appear inclined to overcharge or deceive.

Despite being a dry state, drug use is widespread, affecting both men and women, making it a major social concern. Public awareness campaigns are prominent, with numerous signboards promoting safe sex and educating people about HIV prevention.

Upon speaking with locals, I learned that Mizoram has a higher female population, and outsiders often visit for sex tourism. This has contributed to the need for awareness campaigns. Some locals claimed that around 20–30% of those involved in sex work were HIV-positive, though this was based purely on word-of-mouth accounts.

TRIPURA

Tripura is the third smallest state in India, after Goa and Sikkim. With a population of just over 3 million, it is the seventh least populated state, though it has a high population density similar to Assam, unlike most other northeastern states. While agriculture employs most of the population, the service sector, particularly retail trade, contributes the majority of the state’s GDP.

Tripura has a high literacy rate of 87%, making it one of the most literate states in India. However, its historical records are sparse, with little well-documented information on the kingdoms that once ruled the region.

More than half of Tripura’s population consists of Bengali Hindus who migrated from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) between 1949 and 1972, particularly during the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. This large-scale migration led to tensions and insurgency attacks as the indigenous Tripuri population, which once constituted 62% of the state, declined to just 30%. Bengalis now form the dominant group, making up about 60% of the state’s population. Despite past conflicts, Tripura has remained largely violence-free since 2016.

Among the 19 tribal groups in the state, the Kokborok-speaking Tripuris are the largest, which is why both Bengali and Kokborok are official languages. Around 85% of the population practices Hinduism, unlike some other northeastern states where Christianity is more prevalent.

Bamboo and cane handicrafts are widely used for both practical and decorative purposes, much like in the rest of the Northeast. The state’s cultural heritage is primarily showcased through its diverse tribal dance forms, accompanied by traditional string and flute instruments.

Influx of Bangla people

Before independence, Tripura’s tribal population was around 1.5 million, mostly residing in the hills, while the plains remained largely unoccupied. A common belief among the tribals is that settling in low-lying areas increases the risk of losing their homes and lives to floods, which is why they predominantly inhabit the hills.

During the partition of East Pakistan in the 1960s and 70s, a massive influx of Hindu refugees from Bangladesh settled in Tripura. At the time, the indigenous tribal communities welcomed them warmly, offering them land and resources. Around 2 million Bengalis, far exceeding the tribal population, migrated to the region. While the Bengali settlers remain grateful to the tribals for their hospitality, demographic shifts have led to a shift in political and social power, which now largely rests with the Bengali majority.

Today, Bengalis make up about 65% of Tripura’s population. In the northern part of the state, most Bengalis speak the Dhakai dialect, influenced by the speech of Dhaka, while in the south, the majority are Sylheti-speaking immigrants from Sylhet.

Consequence of the influx

Earlier, education levels in Tripura were quite low, but with the arrival of Bengalis, significant development took place, particularly in education and administration. Today, the Bengali community holds much of the political and economic influence in the state.

Tripura has a distinction between Scheduled Tribes (ST) and the general category, with most Bengalis belonging to the general category. The state offers several benefits to its tribal population, including tax exemptions and various government welfare schemes. Despite Bengalis being the majority, 70% of government job reservations are allocated to the tribal communities, ensuring significant representation in public sector employment.

People

Like much of the Northeast, Tripura suffers from poor transportation infrastructure, which has hindered industrial growth and led to high unemployment. With limited job opportunities, most people either rely on small-scale businesses or compete for government jobs, where intense competition makes securing a position difficult.

The state’s main connectivity, NH8, which links Tripura to Assam, is a single-lane road, much like Mizoram’s, making transportation challenging and slowing development.

Tripura’s literacy rate is often debated. While the official figures are high, much of the education is in Bengali and remains outdated. Many believe the government inflates statistics to showcase progress, while in reality, tribal areas still face a significant lack of educational access. In many government schools, especially in rural areas, a 12th-grade class might have only two teachers managing all subjects.

A notable aspect of Tripura’s population is that many people have never traveled outside the state. This could stem from historical migration experiences, leading to a subconscious hesitation to leave their homeland.

Crops

The queen pineapple is one of the most famous fruits of Tripura, along with jackfruit, which grows abundantly across the state. Jackfruit trees can be seen everywhere, making it a staple in local diets. While the indigenous tribes once practiced jhum cultivation extensively, this method has been declining over the years. Today, rubber and tea have become the primary cash crops, with Tripura ranking second only to Kerala in rubber production.

MEGHALAYA

Meghalaya, meaning “abode of clouds,” is divided into three regions: the Jaintia Hills in the east, the Khasi Hills in the center, and the Garo Hills in the west. Each region is home to its respective tribes—the Jaintias, Khasis, and Garos. The Khasi, Garo, and Pnar languages together account for nearly 75% of the state’s spoken languages, though English serves as the unifying and official language. Meghalaya is the only state in India where English is the sole official language, a legacy of British rule when it was nicknamed the “Scotland of India.”

Historically, Meghalaya has followed a matriarchal system, where lineage and inheritance are traced through women. The youngest daughter inherits family wealth and is responsible for taking care of her parents

Around 70% of the state is covered in forests, making it one of India’s most heavily forested regions. Meghalaya is also the wettest place on Earth, receiving the highest annual rainfall in the world. The economy is largely agrarian, with major cash crops including rice, maize, potatoes, pineapples, bananas, papayas, and spices. Shifting (jhum) cultivation is still practiced, similar to the Kuki tribes of Manipur, Mizo tribes of Mizoram, and Tripuri tribes of Tripura.

A portion of Meghalaya’s forests is considered sacred groves, protected by local tribes for religious and cultural reasons. These forests are home to a vast array of wildlife, including mammals, reptiles, birds, and insects. Meghalaya alone hosts 250 species of butterflies, accounting for nearly one-third of India’s butterfly diversity.

After Nagaland and Mizoram, Meghalaya is the only other state in India with a Christian majority, with 75% of its population following Christianity.

Religion and culture

In the Khasi Hills, a section of the population still follows the traditional animistic faith known as Niamtre, though the majority have converted to Christianity. Around 70% of the Khasi population is Christian, with Catholics forming the largest group.

In Niamtre culture, the rooster is considered a sacred animal, as its crowing is believed to awaken the sun, which, according to legend, had been consumed by evil. Rituals often involve chicken and goat sacrifices as part of their religious practices.

Throughout the Khasi region, numerous monoliths have been discovered, which are considered sacred by the locals. These sites serve as places of worship, where prayers and rituals are conducted by traditional priests.

In the Garo region, a small section of the population still follows the traditional animistic faith known as Songsarek, which, like Niamtre, involves animal sacrifices. However, the majority of Garos have converted to Christianity, with Baptists forming the largest Christian denomination.

Unlike the Khasi Hills, where some traditional practices continue, the Garo Hills have seen a significant decline in their indigenous customs and cultural heritage, with much of it fading over time.

Food

The staple diet in both the Khasi and Garo Hills consists of rice and meat. The indigenous rice variety has a reddish hue, similar to that found in Manipur, and is often mixed with white rice before consumption. Chicken, beef, and pork are dietary staples, while locally grown potatoes are widely used in meals.

Tea is commonly consumed with lunch, and a variety of wild vegetables, including squash, pumpkin, lettuce, and tubers like sohphalang, are part of the diet. While both regions share similar eating habits, the Garo Hills have a broader range of meat preferences, including those found in Nagaland, such as dog meat.

Festival

Seng Kut Snem is a festival celebrated in November to mark the end of the year according to the Khasi calendar. Shad Nongkrem, a traditional dance once performed for the king, continues to be practiced today. In the Jaintia region, Behdienkhlam is observed in October to drive away evil spirits. Meanwhile, the Garo community celebrates Wangala, also known as the “100 Drums Festival,” in November as a harvest festival. While these cultural events hold deep significance, many Christians in the region attend them as spectators rather than active participants.

Education and employment

Meghalaya faces significant challenges in education, with most students opting for arts and commerce, often leading to limited job opportunities. Government jobs remain the primary aspiration, but those who do not secure them typically turn to small businesses, particularly in the food and lodging sector. While tourism is a key revenue generator, the industry remains unstructured and underdeveloped, preventing it from making a substantial impact on the state’s economy.

People

The Garo and Khasi regions of Meghalaya are vastly different, with a river acting as a natural divide between the two. The Garo region is more traditionally tribal in nature. Garos are known for their exceptional cleanliness, with Rangsapara in Assam—home to many Garos—being recognized as the cleanest village in the state. This emphasis on cleanliness is evident throughout the Garo side of Meghalaya as well.

Bamboo houses are a cultural staple in the Garo region, traditionally built on stilts to protect against frequent floods. However, flooding has decreased in recent times, partly due to afforestation, but also as a result of deforestation and illegal sand mining in the lower parts of Garo territory, particularly in Assam.

Across all three regions of Meghalaya, people primarily speak their local languages, making communication in Hindi or even English challenging. However, the Garo region has a relatively higher number of people who can converse in Hindi.

Like much of the Northeast, land in Meghalaya—including the hills—is owned by locals and cannot be sold to outsiders due to the Land Transfer Act. This has led to ongoing tensions between tribals and non-tribals, particularly in Shillong and other larger towns. Curfews are common due to clashes, and local student councils frequently demand the implementation of the Inner Line Permit (ILP) to regulate outsider settlements. The fear of land being taken over by non-tribals, referred to as “Dekhars,” remains a significant concern among locals.

Meghalaya follows a matriarchal system, where women inherit property, and after marriage, men move into their wife’s home. Women are actively involved in running businesses, often managing shops and markets. Despite the language barrier, they were incredibly warm and hospitable—some even refused to charge me for food. However, men also contribute equally to the workforce, working alongside women in various fields.

SIKKIM

Sikkim is the second smallest state in India after Goa and the least populated in the country. Nearly 80% of its land falls under the state’s forest department, making it a heavily forested region. Although historically ruled by the Buddhist Namgyal dynasty, Sikkim is a multiethnic and multilingual state. Hinduism is the predominant religion, followed by a significant Vajrayana Buddhist population.

Agriculture and tourism are the backbone of Sikkim’s economy. The state cultivates maize, wheat, rice, barley, oranges, and cardamom as major cash crops. However, due to the region’s rock composition, Sikkim is highly prone to weathering and erosion, leading to frequent landslides. Despite this, it boasts rich biodiversity, housing nearly 700 of India’s 1,400 butterfly species.

Sikkim is also one of India’s most environmentally conscious states. It banned plastic water bottles throughout the state and, in 2003, committed to fully converting to organic farming—a goal it successfully achieved by 2015, making it India’s only completely organic farming state. Additionally, in 2008, Sikkim became the first state to achieve 100% sanitation coverage, eliminating open defecation entirely.

The state’s Gorkhali majority celebrates all major Hindu festivals, while the Buddhist population observes their own traditional festivities. Noodle-based dishes and momos are staple foods, and Sikkim has a notably high alcohol consumption rate, ranking just behind Haryana and Punjab.

Influx of outsiders

Before 1975, Sikkim’s population was around 1.5 lakh. However, due to a significant influx of Biharis, Marwaris, and Nepalis, the population has grown to nearly 7 lakh today. The state government allowed those who had settled in Sikkim before 1975 to retain their land and even granted them the right to bring their relatives to settle in the state under a lease system.

As a result, it has become difficult to find indigenous locals in urban areas, as many have moved to remote corners of the hills. Meanwhile, Biharis, Marwaris, and Nepalis dominate the business sector, shaping the state’s economy. These communities have also brought their cultural traditions with them, celebrating Hindu festivals in Sikkim just as they would in their native regions.

Education and employment

The locals in Sikkim tend to pursue education only up to the level required for securing government jobs, as the state government reserves these positions exclusively for them. Interestingly, the government has ensured that at least one individual from every local family is employed in the public sector. Even those with minimal education are provided with jobs, such as maintaining cleanliness, to prevent unemployment among the indigenous population.

Meanwhile, outsiders largely forgo formal education and focus on business ventures. Sikkim’s economy is heavily dependent on tourism, with a vast number of hotels and homestays operated by both locals and migrants, making it the backbone of the state’s livelihood.

The place

Sikkim is an exceptionally peaceful state with an extremely low crime rate. People live in harmony, with most having found stable job opportunities. Law enforcement is strict, ensuring that rules are followed diligently. Even simple regulations, like the ban on open smoking, contribute to maintaining cleanliness.

However, despite these efforts, I noticed that the widespread consumption of pan masala and the habit of spitting have somewhat undermined the state’s otherwise pristine environment. Traffic discipline is commendable—despite the narrow roads, people drive sensibly and rarely honk. Roadside posters encourage motorists to refrain from honking, further adding to the state’s calm and orderly atmosphere.

Interestingly, each district in Sikkim has a designated weekly closure day when all government offices and public sectors remain shut. For instance, in Singtam, this day falls on Wednesday. The government assigns a specific day for each district, ensuring a uniform break across various sectors.

Despite its relatively low population, Sikkim feels quite congested and crowded. Buildings are permitted to rise up to five stories, creating more residential and commercial space but also contributing to a cramped urban landscape, especially in city areas.

People and government

Sikkim is home to some of the warmest, most hospitable people in India. The locals are welcoming, kind, and deeply rooted in their traditions. Hospitality is second nature to them, which is why homestays are such a popular way of hosting visitors. However, they are generally reserved and follow societal norms diligently.

One of the most striking aspects of Sikkimese hospitality is their willingness to accommodate outsiders. Many non-locals have been able to establish businesses in the region without resistance. While the people of Sikkim excel in hosting guests, they are not as adept at business and marketing. Many homestays, for example, are not even listed on maps because the owners are unfamiliar with digital tools. Despite this, they continue to provide exceptional hospitality, often offering more than their own means allow in the hope of earning a modest income. Their kindness and generosity make them some of the sweetest people one can meet in India.

Their simplicity, honesty, and humility are deeply tied to their religious beliefs. Whether Buddhist or Hindu, most people in Sikkim strictly follow their faith. The philosophy of *Atithi Devo Bhava* (meaning “Guest is God”) is ingrained in their way of life. As a mark of respect, guests are often served meals in brass plates, a gesture that reflects their deep-seated values.

The government has been actively promoting tourism by providing free homestays for lower-middle-class families. However, government jobs do not pay much, and most people do not live extravagant lives. In remote villages with little tourism, farming remains the primary livelihood. Many villagers live in mud and bamboo houses and lead simple lives similar to rural communities across India. While employment opportunities have provided some financial security, they have not necessarily improved living standards.

Agriculture in Sikkim is mostly for self-sustenance rather than commercial gain. Farmers grow food for their own consumption and rarely sell their produce, except for a few items like ghee, ginger, and broomsticks. They do not view farming as a profit-driven enterprise. However, the quality of their food is exceptional—organic, medicinal, and free from synthetic additives. Many elderly people in Sikkim remain fit and healthy, thanks to their nutrient-rich diet. The only packaged items they commonly use are oil, salt, spices (which were previously avoided), flour, and occasionally sugar. Even tea is traditionally prepared with salt instead of sugar.

Sikkimese people have a deep understanding of herbal medicine and the benefits of organic food. However, organic farming has its challenges. Some farmers mentioned that crops like cardamom, ginger, and mustard, which once flourished, are now struggling due to microbial infections. They believe locally grown mustard oil is far superior to packaged versions, noting its ability to soothe coughs and create a burning sensation when consumed raw—something commercial mustard oil does not replicate.

Despite these challenges, Sikkim remains one of the cleanest and most environmentally conscious regions in India. The use of plastic is minimal, and traditional bamboo utensils are still common. Bulls are used for plowing fields since tractors are difficult to operate on hilly terrain. The people of Sikkim breathe some of the cleanest air, drink pure water, and consume highly nutritious food.

However, Sikkim is also prone to natural disasters like landslides, earthquakes, and floods. The government provides compensation whenever disasters strike, but the challenges persist. One of India’s longest-running landslides has been active in Sikkim for the past three years, cutting off the road between Yangang and Ravangla.

In many ways, Sikkim offers a rare balance between tradition and nature. While challenges exist—whether in business, farming, or disaster management—the warmth of its people, their deep-rooted values, and their connection to nature make the region truly special.

My travels through Northeast India felt like drawing just a bucket of water from a vast lake—there is so much more to explore and understand. Among the four broad regions of India—the South, North, Extreme North, and Northeast—the Northeast stands out as the most diverse. Its complexity is difficult to grasp fully, as governance, administration, and business each offer their own perspectives, sometimes complementing and at other times contradicting one another.

Much like Ladakh, which I’ve written about in another article, the Northeast has something for every type of traveler. My observations are based on what I experienced from the perspective I had while traveling, but they could have been entirely different had I taken another route or visited different locations. I encourage you to take this article as just one perspective, to explore further, and to add your own experiences to the narrative. For insights into my travels across the rest of India, you can check out my summary here.

I am a 31 year young PhD graduate who has decided to travel the length and breadth of India on my cycle, to document the journey of meeting a vast array of people. In my journey, I intend to understand the characteristic features of the people of this nation and categorize them based on their demographics, age, profession, gender, traditions, and cultural differences.